Note

This page is the group-generated report of our project. Please access each of our individual reflexive analyses using the menu on the left side of the page. You may also explore the categorized images using the taxonomy below the menu.

A Digital Storytelling Project for EDCP512

Data Collection

To contribute to the larger research question that asks “How can we create an environment as graduate students (part-time and full-time) within our Faculty of Education courses that builds a sense of belonging and community?,” our group employed digital storytelling as an arts-based research method to conceptualize and define “community”.

The first stage of data collection involved our co-researchers submitting images and accompanying text components to this website we created to guide the direction of the data collection and tie it to our purpose of defining “community,” we established three categories of images as “prompts” for our co-researchers:

- An image that represents a barrier to community,

- An image that doesn’t include humans and represents community, and

- An image that is primarily one colour that represents community.

Co-researchers added text components for each image they uploaded in the forms of a title, tags/keywords, and a brief rationale or description explaining their image choice. While the images and titles are visible to the public on this website, the brief rationalie is only accessible to the researcher group.

The second stage of data collection took place in class on November 5th, 2019 with the purpose of defining community more narrowly in the context of Faculty of Education classrooms highlighted in our research question. We conducted a 1-2-4-All exercise from Liberating Structures with our co-researchers, outlined at this link.

We began by asking the whole group to individually reflect on the submitted images, examples of which are in the slider below, then form pairs to discuss the three pre-established categories. Later, these pairs formed groups of four to create new categories that could better encapsulate the representation of “community” in the classroom. With this exercise, we intended to both engage our classmates in the driving of our research design and test the assumptions embedded in our existing categories. We recognized this as an essential step to meet the criteria of rationality, sustainability, and justice in participatory action research (Kemmis, McTaggart & Nixon, 2014).

Data Analysis

Our group divided up into three sub-groups to analyze the data. The first group (Andrea and Shuling) looked specifically at the images submitted to the website; the second (Chi and Mingyu) examined the text components that accompanied these images; and the third (Colin and Waylon) were tasked with recategorizing the uploaded images into the new categories formed by our class and compare all categories (existing and new).

Text Analysis

Chi and Mingyu conducted a thematic analysis of the keywords and phrases we had highlighted from the text data. We perused the titles, tags, and descriptions submitted with the images to identify common themes or topics, as well as any associated tones or connotations. Our analysis is guided by both inductive and deductive coding principles, relying primarily on the former as we took note of new themes emerging from the data. Once the themes were established, we connected them to a set of questions based on the 5W1H (what, who, when, where, why, how) framework to help conceptualize “community.”

Image Analysis

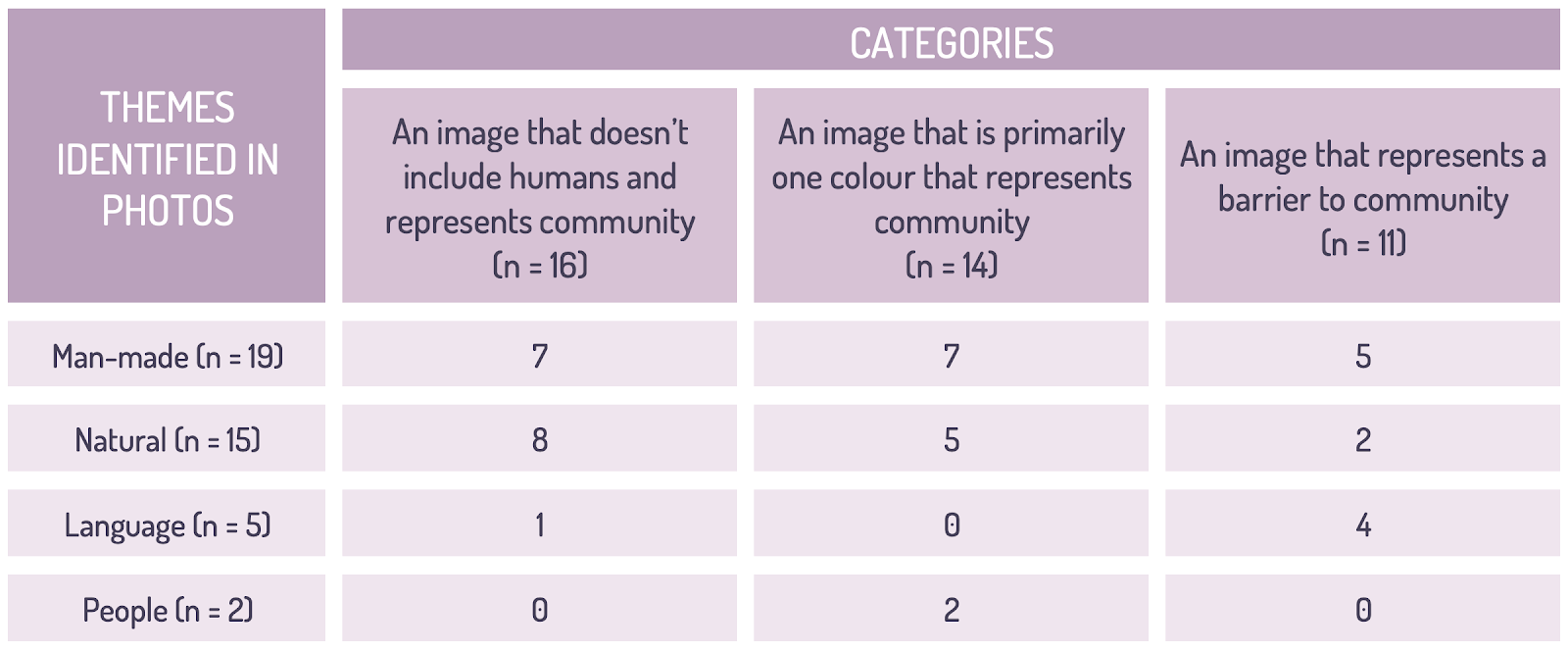

Shuling and Andrea completed a thematic analysis of the 41 images collected on the website. Four general themes (e.g. man-made; natural; language; people) were chosen as nominal variables after a review of the images. Each image in the original three categories was individually coded with the most appropriate theme. For example, the image below was coded as "natural". A contingency table depicts the frequency count of each theme in the three categories (Appendix A).

Category Analysis

In order to mirror the initial data gathering process, where co-researchers submitted images according to prior constraints, Colin and Waylon used three of the four new categories (one new category was discarded because it was redundant) suggested in the November 5th class to re-categorize the images that had been submitted. This allowed us to constrain ourselves to analyzing the images within the feedback provided by all co-researchers. During class on November 12th, we worked together to re-categorize 8 images in order to calibrate our individual work. Following that, we each categorized another 17 images individually. The image below, for example, was recategorized into the new categories "Images with people" and "Images before, during, and after the class".

The re-categorization of images was more challenging than we thought it would be. It initially appeared to be a relatively simple process of categorizing the images with new categories more suited to thinking about educational communities. Once we began, however, we noticed an overlap between two of the new categories “non-human community of practice” and “non-human living things”, so we decided to combine both into one category: “An image that doesn’t include humans and represents your community of practice”. During our analysis, we also developed two new categories: 'weaponized community' and 'silent people' (Mazzei, 2007).

Results

Results of the Text Analysis

The analysis of the text data produces seven main themes and multiple sub-themes in relation to community: synonyms, qualities, barriers, action/activities, entities (humans, animals, plants, objects, food), context (time, space), representation (visibility, colors). These themes are then further linked a series of questions to help conceptualize “community”:

- What is a community? (synonyms, qualities)

- What is NOT a community? (barriers)

- How to create a community? (action/activities, context)

- Who and what create a community? (entities)

- Where and when does a community exist? (context)

- How to describe a community? (representation)

The first question (What is a community?) and its associated themes often provoke a positive tone, while the second question (What is NOT a community?) a negative tone. For example, the qualities that signify a community are a mix of nouns and adjectives with positive connotations, such as “safe”, “inviting”, “harmony”, “comfort”, “balance”, “interconnected”, “sustainable”. The barriers, in contrast, are more negatively charged (e.g., “tension”, “strain”, “non-inclusive”, “exclusivity”, “separation”, “hard to connect”). The remaining questions are linked to primarily neutral key words and phrases (i.e., objects, entities, places, activities, etc.). Our findings are summarized in a series of tables (below).

Summary of Text Data

Table 1: What is a community? – Some synonyms and qualities of a community (positive)

Table 2: What is NOT a community? — Some barriers, including division, invisibility, distance, economic gap, and some entities (negative)

Table 3: How to create a community? — Some actions that build community, and some contexts (positive – neutral)

Table 4: Who or What create a community? — Some entities that create a community (neutral)

Table 5: When and Where exists a community? — Some contexts, spaces, and activities (neutral)

Table 6: How to describe a community? — Visibility and colors (neutral)

Results of the Thematic Image Analysis

The thematic photo analysis revealed some similar results to the text analysis. There was a common theme of nature throughout the three categories of photos. The emphasis of natural themes in the photos suggests that our co-researchers perceive links between nature and their conceptualization of community. This parallels Collins’ (2004) definition of the ecological approach to the ethics of collaboration inspired by interconnected and holistic natural systems. Language, a theme based on communication, appeared mostly in photos under the category of “an image that represents a barrier to community”, implying that language may be regarded as an obstacle to building community. Lastly, out of the 41 photos, only two were coded with the theme of “people”. This aligns with our research team’s hypothesis that our categories had unintentionally encouraged our co-researchers to share photos without people in them. This was a critique brought to our attention by our co-researchers during our November 5th in-person data collection. Additionally, co-researchers expressed privacy concerns about posting photos of people to our public data collection website.

Summary of Thematic Image Analysis Data

Table 7. Contingency table summarizing the frequency of themes identified in the thematic analysis to the three categories into which co-researchers sorted their images.

Results of the Category Analysis

Another outcome of the process was that we identified two emergent categories in the images. First, as we began, we noticed that there were only 2 images tagged “with people” (ie. there were only two images that contained people), but 12 images in the “silent people” category after the re-categorization. Recalling Mazzei’s (2007) admonition to “engage the silences as meaningful and purposeful elements of these texts”, we began to consider that the absence of people in images that might normally contain people (a sunny park) might be significant (p. 634). Our focus of “with people” switched from the physical presence of people to the social and emotional content of non-human images that speak to community in some way through the absence of people. Examples of this category are shown in the slider below.

The second emergent category was ‘weaponized community’. There were 5 images originally categorized as ‘barriers to community’ where the barriers seemed to be actively constructed to intentionally exclude ‘others’. Exclusions were based either on gender non-conformity or income and social status. Samples are shown below.

Discussion

Returning to our original goal of discovering how to create community within our Faculty of Education courses, we offer the following recommendations:

- Based on our process of re-conceptualising 'community' in the absence of people, we recommend incorporating, as much as is reasonable, interaction with the natural world.

- In addition to recognizing and removing passive barriers to community (time and distance), we must ensure that we do not weaponize community by actively constructing barriers to participation, especially those which target the exclusion of already marginalized people.

- Community is built through actions and intentional activity; we should design courses to maximize learner interactions and cooperation.

- Eating together is a socializing act of community.

- Be aware and intentional about invisible people in the community.

- Enabling asynchronous interactions through text-based digital tools can encourage English Language Learners to participate more fully in educational communities.

Future Research

Our results reveal how our co-researchers perceive and conceptualize community broadly. Initiated by our in-class activity, further research could investigate if our results are also applicable to our co-researchers’ conceptualization of community in Faculty of Education classrooms at our university.

References

Collins, S. (2004). Ecology and ethics in participatory collaborative action research: An argument for the authentic participation of students in eduational research. Educational Action Research, 12(3), 347–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790400200255

Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R., & Nixon, R. (2014). The action research planner: Doing critical participatory action research. Singapore Heidelberg New York Dordrecht London: Springer.

Mazzei, L. A. (2007). Toward a problematic of silence in action research. Educational Action Research, 15(4), 631–642. https://doi.org/10/dfp2zp